By Thor J. Mednick, PhD

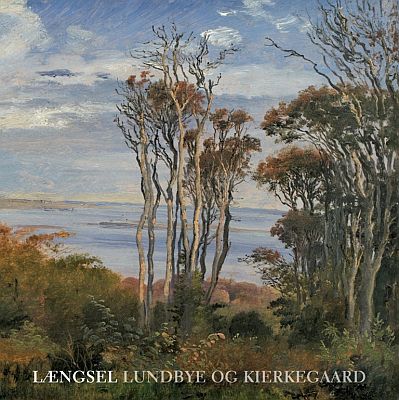

This richly illustrated catalogue, which informatively examines the well-documented influence of Søren Kierkegaard (1813-55) on Johan Thomas Lundbye (1818-48), accompanied last year’s exhibition of the same title and was released to coincide with the bicentennial of Kierkegaard’s birth.

It is no doubt fitting that such a catalogue should begin with a celebration of Lundbye by Hans Edvard Nørregård-Nielsen, a stalwart champion of the Danish Golden Age whose tireless pursuit of Lundbye’s physical and intellectual traces have done so much both to consolidate the latter’s biographical and professional record and to make irrevocable his setting in the diadem of Danish national romanticism. Here, as elsewhere in his work, Nørregård-Nielsen wishes us to understand Lundbye not just as a painter who thought insightful thoughts, but as the painter of those thoughts, and not just as an artist from Denmark, but as the artist who was Denmark. “He loved his mother and the Fatherland as though they were one symbiotic entity,” posits Nørregård-Nielsen, and from the very beginning, Lundbye’s art and his writings came together to form

a national treasure; some of it is as fresh and crisp as the summer or winter that bore it, while some seems more tired, fed-up beyond tolerance with familiar complaints.1

(Nørregård-Nielsen, p. 25)

While Nørregård-Nielsen finds examples of fresh and crisp submissions throughout Lundbye’s painted oeuvre, it appears that the reference to “familiar complaints” derives mostly (or exclusively) from the artist’s copious letters, journals, and notations. A curious aspect of Nørregård-Nielsen’s remarks is thus the two-fold assumption that underlies them: 1) that one must know Lundbye as a person in order to appreciate his artistic program; and 2) that in the analysis of Lundbye’s art, his correspondence and diaries have the same explanatory or associative power as the art itself – that all of these sources are essentially interchangeable as evidence. It should be noted that this approach to the study of Lundbye is not original to Nørregård-Nielsen, nor can he be regarded as responsible for it. Notwithstanding the new art history (which is not all that new anymore) the methodology of Lundbye scholarship remains significantly biographical, and the analysis of his art remains substantially dependent on the content of his own writings about it.

There are, certainly, some merits to this practice. For instance, the fond respect with which Nørregård-Nielsen remembers the artist and his work, in Længsel, produces a succession of visual analyses as seductively cohesive as they are comfortingly wholesome. There is a complication, however; for while the treatment of Lundbye has emphatically established his significance in the history of Danish art, it has sometimes done so in a rather circumscribed way. When Lundbye’s art is seen as primarily relevant to his writings, and vice versa, and when both are assumed to be directly and organically determined by his biological and national roots, the result can often be tautological, making it difficult to contextualize his output within larger cultural and international trends. An important virtue of Længsel is the effort the authors make to acknowledge some of these larger connections (for instance, the relationship of Lundbye’s art and mindset to European Romanticism) and to engage a rigorous and useful analysis of one of them, in particular: his intellectual interaction with the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard.

All three principal authors of this catalogue are quick to concede that Kierkegaard’s importance for Lundbye’s written reflections is widely acknowledged, but they also express concern that the structure of Kierkegaard’s influence – for instance, what Lundbye actually learned from the philosopher – has not been articulated as precisely as it could be. The authors thus intend Længsel as a corrective to this shortcoming in the present literature, and their contributions to that end are both substantial and robust. Several points of deep inquiry are explored in these essays; for the purposes of this review, however, I will summarize a single, hopefully representative sample. As indicated by the catalogue’s title, the relevance of Kierkegaard’s work for the deliberations that hounded Lundbye for most of his adult life focused especially on the phenomenon of longing. As used here, longing denotes a feeling profoundly desirous and yet just short of actual need, directed at some thing, notion, or idea whose attainment the subject believes would satisfy his longing and thereby render that longing superfluous.

As Bente Bramming demonstrates in her essay, “Længsel hos Lundbye,” Lundbye’s longing expressed itself in a variety of discontents, all of which tended to communicate his perception of a basic, common problem: He seemed not to be at one with himself, as it were, which either resulted in or derived from the feeling of never being entirely at home in the world. As Bramming persuasively explains, Lundbye seemed forever to be torn between, on the one hand, his memories of the uncomplicated life of childhood and mother and, on the other hand, by his hope for a moment when he would achieve greatness as an artist. He longed to create an art that was truly transformative, for himself as much as for his audience: an art that recaptured something of that simplicity and immediacy that had been lost after childhood. In short, Lundbye’s idea of personal happiness was locked, by his own formulation of it, in an irretrievable past and an elusive future.

One cannot help observing in this that Lundbye’s experience of longing was in fact quite typical, in that it was behaviorally autonomic, generated more by internal stimuli than by anything actually external to him. This may suggest some alternative interpretations of his private writings, particularly as they relate to his artistic production. For instance, while his tirelessly professed devotion to the Fatherland may have emerged to some degree from genuinely romantic feelings (whatever that may mean), it is at the very least possible that it emerged as much from the need that his particular brand of maladaptive narcissism generated in him to construct and pursue unattainable ideals. As such, his psychic disquietude might have been in part a simple and reliable device to keep himself working.

At any rate, Bramming observes that the dichotomy of memory and hope, past and future, that ceaselessly pulled at Lundbye left him in a state of alienation from the present, which made it difficult for him to engage fully with life as he was ostensibly living it. It was, therefore, a revelation for him to read Kierkegaard’s Enten – Eller, particularly the passage entitled “Den Ulykkeligste” (“The Unhappiest One”), in which Kierkegaard provided an existential description of precisely this state.2 In Bramming’s words, “the unhappiest one is he who locates his ideal, his life’s meaning and self-fulfillment, beyond or outside of himself” (Bramming, p. 110). He is, as Kierkegaard summarizes it, “always abstracted from himself, never fully present within himself” (Bramming, p. 110). What is important about Lundbye’s encounter with Kierkegaard, beyond the spate of journal entries and letters it inspired the former to write, was its indication to him that he was not alone in his dilemma. Indeed, what Kierkegaard initially afforded Lundbye was simply the validation of a more sophisticated language with which to understand and communicate the thoughts and feelings he had already developed on his own.

Længsel: Lundbye og Kierkegaard contains the following texts:

Hans Edvard Nørregård-Nielsen, “Grundende på den resignation”

Bente Bramming, ”Længsel hos Lundbye”

Ettore Rocca, ”En Ny Umiddelbarhed: Søren Kierkegaard læst af Johan Thomas Lundbye”

Johan Thomas Lundbye, ”Lille afhandling om kunst”, ”Lille afhandling om skønhed”, ”Dagbog 9. december 1846 – 15. april 1848”, ”Tre digte”

Kierkegaard did more, however, than merely elucidate a state of mind that Lundbye already knew. In the first instance, Kierkegaard provided Lundbye with a mechanism to cope temporarily with the profound feeling of loss that he continually experienced. According to Kierkegaard, the way to negotiate the interval between oneself and one’s dearest wishes was in resignation: the sometimes precarious balance between willfulness and self-control that allowed one to reconcile oneself to the unattainability of the ideal, and in its absence do the best one could with what was left. Closely paraphrasing the philosopher, Lundbye described resignation as a “sacrificing of the best, but, as well, an ability with work and contentment to do the next best nearly as well” (Rocca, p. 164).

In the final essay of the catalogue’s first part (part two is given over to Lundbye’s own writings), Kierkegaard-scholar Ettore Rocca presents a magisterial and eminently readable analysis of Kierkegaard’s writings as they relate to Lundbye and of Lundbye’s own interpretations of the most salient passages. Rocca’s cogent distillation of these texts and their relationship to Lundbye’s artistic program is recommended to those who wish to learn more about this field of æsthetic inquiry. One fact that emerges from Lundbye’s diaries and letters is that while the notion of resignation was helpful for him, it was ultimately unsatisfactory because he was unable to relinquish his hopes for himself and his work. Lundbye’s attempt to sublimate his need to achieve the transcendent greatness of simplicity – of immediacy as Rocca specifies it – left him in a somewhat torturous limbo of ambivalence, until, as Rocca relates, he discovered Kierkegaard’s writings on faith, and began to see

em>the miracle that he hoped Søren Kierkegaard could perform: to lead him through deliberation to faith… To be lead to faith meant for Kierkegaard to attain a new immediacy after deliberation; for faith is a new immediacy

(Rocca, p. 153)

In the end, the reader is left with his own unattainable desire: to know how Lundbye’s work under Kierkegaard’s inadvertent guidance resolved itself. It didn’t, at least in part, because of Lundbye’s untimely death. Perhaps, failing this final insight, it is for us to engage our own resignation and learn from what is left us. This catalogue makes a productive place to begin.

Notes

1 Lundbye’s protracted bouts with depression are painfully and repeatedly described in his correspondence and diaries; such entries are central to the analyses of his written work offered in the catalogue under discussion. Some of these, including two public lectures and the third part of Lundbye’s final diary, are published in their entirety for the fist time, in this volume.

2 The very terms “hope” and “memory”, in fact, are Kierkegaard’s.